Twins Video

---

This is an edit to clarify a few points that were made previously that may have been confusing.

I did a bit of research to see whether it will pass the stink test, and so looked at Omar Visquel's Gold Glove seasons (1994-2001). Visquel's percentage of putouts that occurred during double plays (DP/PO) was 40%, so I concluded that Vielma's 39.6% was indeed encouraging. Furthermore, I used this metric as supportive of what I have seen with my eyes this season to suggest that Jose Polanco, with a 52.3% DP/PO rate, despite the rumors, is a very good fielding shortstop. This resulted in a major upset on the top 10 of my Twins prospect list, and a hearty discussion of the metric, among other things, here.

Conceptually it is very simple metric: An effective shortstop will turn more batted balls into outs than a less effective shortstop. It is affected by many things like range and arm, but it is not perfect. It misses the number of chances for double plays as a normalization, and it does not help describe how the shortstop was with the glove when there were no putouts. So I did three things :

a. When I first thought of this, I thought that putouts were the way to go, because for some reason it helped tell more about a shortstop than assists. After a bit of discussion and noodling, this is not really valid. I was wrong to use putouts for the denominator. I think that total chances (TC) are a better denominator, so that is it. Instead of percent of putouts that were DPs, I am using percent of total chances that resulted in double plays (%CDP, from the DP/TC formula)

b. To add something into the measurement that describes a shortstop in a non-double play situation, I went back to an old (and tired) friend and gave it new life by marrying it with %CDP. This is fielding percentage (FP), which by itself is inadequate to wholly describe fielding, but is a very simple conceptual metric: Errors over chances. So this compound measurement is simply: The percent of total chances that resulted in double plays multiplied by fielding percentage, or FP. Because that is a mouthful, I am calling it shortstop fielding effectiveness, or SSFE. (The name is similar to the other metric I devised to simplify pitching effectiveness: Pitching Effectiveness.) For the equation-inclined: DP/TC x FP=SSFE.

c. To normalize for the chances of a double play, or what percentage of total chances were with a man on base, I normalized against the league for a full season, assuming that the chances for a double play are pretty much the same for all teams over the course of 2280 games (152 times 15). A league normalization would be good enough. So I calculated the average SSFE (which was 13.5) and divided each player's SSFE by that average, resulting to a normalized value, which I call nSSFE. A nSSFE of 1 is average, everything above 1 is above average and everything below 1 is below average. To make it look numerically a bit more familiar (think ERA+ and OPS+,) I multiplied by 100, making the average 100, like those other two metrics, creating what I call nSSFE+ (still a mouthful). 139 players played shortstop in the bigs in 2014.

Does it pass the stink test?

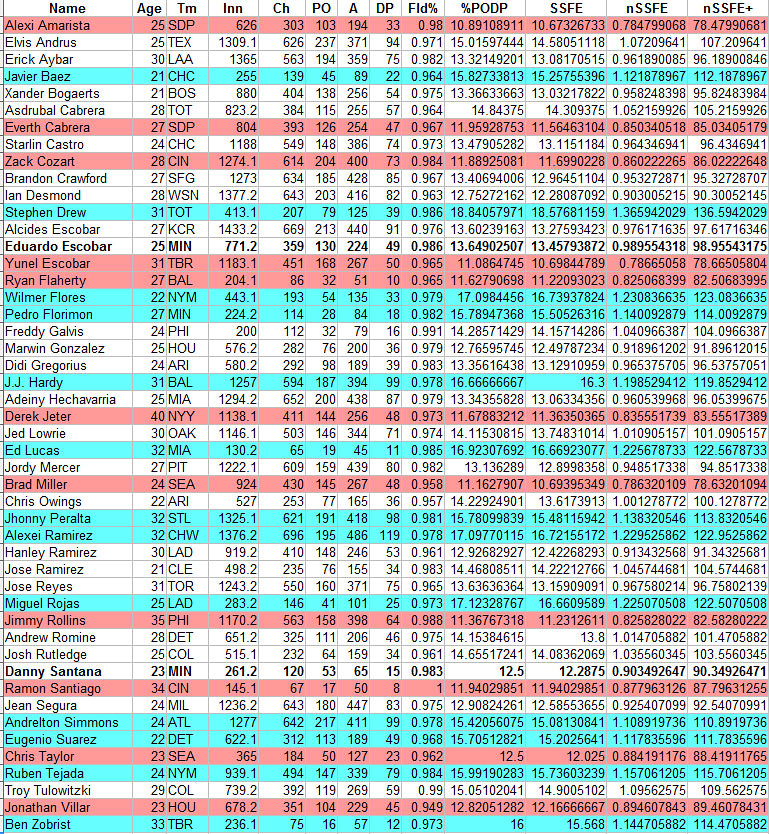

Here is the nSSFE+ for all MLB shortstops in 2014 with more that 200 innings at short. In blue are the above average shortstops (nSSFE+ 110 or more) and in red are the below average (nSSFE+ 90 or less.) Since this is a Twins-focused blog, the Twins' players are in bold.

I think that it does pass the stink test if you look who are in the blue categories (JJ Hardy, S. Drew, et al) and who are in the red (Derek Jeter, Jimmy Rollins et al.)

Is it a perfect metric? No; because there is no such a thing. But I think that it is easily understood and can be valuable. And it is better than the "eye" alone. The two together may be awesome. Could it be translated to other positions? I will try to play around, but feel free to play and tell me ![]() I will eventually look to see how the average moves with history, and potentially refine it, but this is the first attempt.

I will eventually look to see how the average moves with history, and potentially refine it, but this is the first attempt.

Originally published at The Tenth Inning Stretch

MORE FROM TWINS DAILY

— Latest Twins coverage from our writers

— Recent Twins discussion in our forums

— Follow Twins Daily via Twitter, Facebook or email

— Become a Twins Daily Caretaker

Recommended Comments

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.